Ethos III: The original virtue was for men.

Aristotle made virtue the most powerful characteristic of a leader. So why did it take women so long to acquire it?

In my last two posts, I explored two of the three characteristics of an ideal leader and shared how I found myself wanting in each. My Uncle Ward showed perfect eunoia, or disinterest, when he sacrificed himself in the sky over the English Channel. The film Money Ball illustrated how the second trait—phronesis, or practical wisdom, often clashes with the values of your audience. My own pragmatism led to misery at a corporate job.

Then there’s the king of ethos, virtue. Aristotle wrote that the audience’s belief in your goodness—holding the same values and nobly living up to them—defines arete, or virtue. It’s the most powerful leadership trait of all, which explains why we frequently vote for people who aren’t particularly qualified. In fact, virtue divides American more than any other factor. When we vote for our values, we acknowledge our membership in the tribe that holds them. The more tribal we get, the more important virtue becomes. And we have become deeply tribal.

This isn’t new. Ancient Romans—enthusiastically tribal sorts (tribes were voting groups) supported the most virtuous men. And by “virtuous” they meant manly. (As I pointed out previously, Vir is Latin for “man.”) When Gladiator Russell Crowe utters “Strength and honor” before going into battle (Virtus et honoris is the most common translation), he might just as have been saying “Manliness and honor.”

Sidebar: I’ve found lots of amateur content asserting that the Roman army used “Strength and Honor” during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. But I can’t find any reliable scholarship confirming that. Russell Crowe claimed that he came up with the expression for Gladiator, based on the motto of his all-boys high school in Sydney, Australia, Veritate et Virtute (“Truth and Honor,” or, more accurately, “Truth and Manly Honor”). He wisely changed “Truth” to “Strength,” and director Ridley Scott enthusiastically accepted it. Thus the myth was born.

Hollywood aside, the Romans and their Greek forebears did equate honor and manliness. That’s because back in the day, women had little agency. Being under the direction of men, they were incapable of initiating their own significant actions, except in dishonorable disobedience. Aristotle wrote that character reveals itself through the person’s actions; if you’re not responsible for your own noble behavior, then you cannot act honorably.

Virtue only became a female quality in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when women began to take on a degree of standing. But womanly honor mostly meant behaving themselves sexually: saving themselves for marriage, virtuously fighting off untoward advances, and staying “faithful” to their randy husbands. By Victorian times, virtue had taken on so much sexual-purity baggage that men wanted nothing to do with it. A virtuous person could only be a woman.

And yet Aristotle’s rhetorical theory of virtue survives, and I think it helps explain why women have such a hard time getting elected. We still admire womanly virtue, though these days that essentially means being the opposite of a “bitch” (assertive, ambitious, devious). Manly virtue has kept much of its ancient meaning (assertive, ambitious, courageous). But don’t you dare call a man “virtuous”! Instead, a rhetorically virtuous fellow is a “good man.” A “good woman” is different. We may love her, put her on a pedestal, and call her saintly. But that wouldn’t earn her votes.

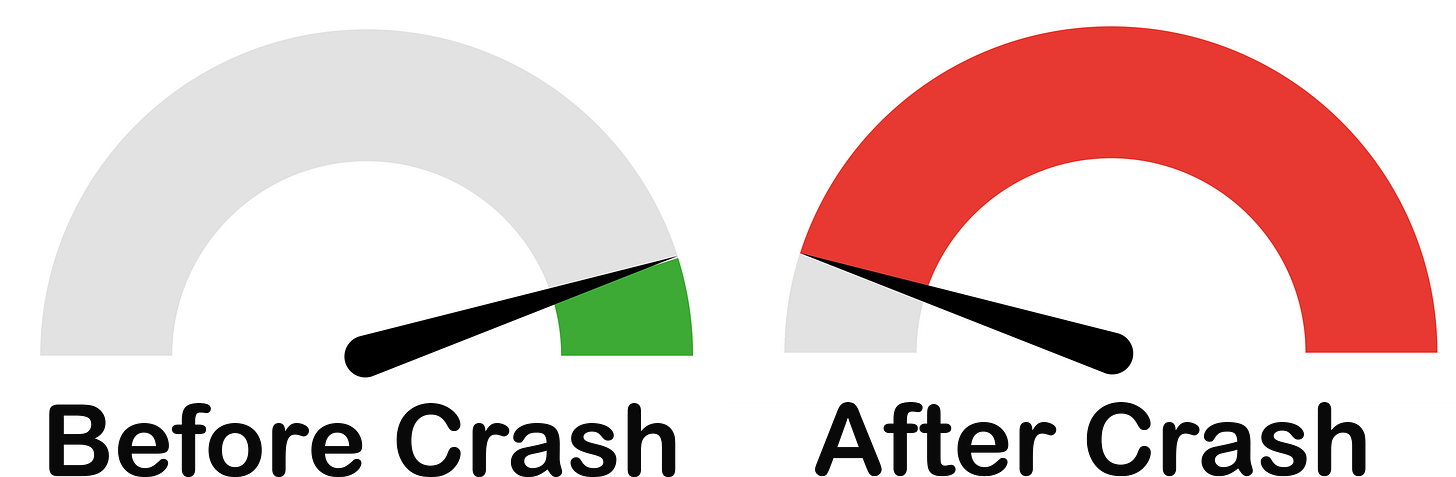

Even a “good man” is good only for his particular place, time, and tribe. To illustrate that, I’ve rated the virtue of past presidents, with “1” being rotten to the core and “5” being perfectly virtuous. You’ll see how the most important trait of ethos isn’t all that stable.

George Washington: Most of his contemporaries would give him a 5. You don’t get more manly than fathering a country! (Today, that slavery thing would push the needle way down the Virtuometer.

Abraham Lincoln: He ran for office as “Honest Abe,” the log-cabined Railsplitter. Virtuous stuff, it played to the values of a rurally nostalgic culture. Lincoln didn’t have much going for him in the phronesis line. His resume—corporate lawyer, failed Senate candidate—lacked umph. But many thought him a Good Man. His supporters would have given him a Virtuometer score of 5. His opponents, on the other hand, were shocked by the idea that the government might choose to violate the Constitution’s protection of personal property by freeing their slaves. Antebellum America was a divided tribal culture. Southerners would push Virtuometer rating well into the red. You might even say that Lincoln’s virtue sparked the Civil War. Today he gets mixed reviews, depending on how you feel about his attitude toward Blacks as full participants in our society.

Herbert Hoover: Unlike Lincoln, Hoover seemed almost overqualified for the presidency. He had phronesis galore. A wealthy mining engineer, he ran the U.S. Food Administration during the First World War, aiding both Americans and allies. When the war ended, he led relief efforts in Europe, earning headlines for his compassionate efficiency. He served as Commerce Secretary for seven economically booming years—pushing the brave new technologies of air travel and radio—before winning the 1928 presidential election in a landslide. Before he entered the White House, his Virtuometer dial was springing waaayyy into Good Man territory. And then came the Depression. He blamed Mexican immigrants, forcing the repatriation of some one million people while refusing to use government levers to relieve the Depression. By the time he ran against FDR in 1932, Hoover’s meter was in deep in Bad Guy territory.

John F. Kennedy: War hero, family man, great orator, best-looking President since Warren Harding, martyr. He wasn’t that successful in getting bills through Congress, though, and there was that Bay of Pigs fiasco. So, while not that high up in the phronesis department, he enjoyed a sparkling virtue for more than decade after he was assassinated. Then the stories of his sexual escapades came out.

Donald Trump: I’ll leave this to you. Ignore him altogether or think about how, in purely rhetorical terms, supporters might consider him virtuous. The election shows that clashing values over religion, language, sexuality, education, traditions, and institutions—the stuff of virtue—can determine an election.

Now rate your own virtue. Did you find yourself saying “That depends?” Good! Your virtue to a colleague might look different from your virtue to a loved one. Or to your pet. Or depending on whether your pet is a dog or a cat.

Put your own slogan in the comments.