How to Talk to Yourself

I learned to practice the ancient art of persuasion by making friends with the voice in my head.

All my life I’ve talked to myself. I was a little embarrassed about the fact and never shared that secret—until I read The Odyssey and discovered that its main character, noble, hard-bodied, silver-tongued Odysseus, did the same thing.

“Two counsels warred within me: one bade me put to sea through the straits of Scylla’s rock, lose six men but save the rest—yet the other cried steer closer past Charybdis’ maw.”

Odysseus seemed to talk to himself only when he was out of earshot of the other Greeks. I learned at an early age to do it silently.

Lots of people talk to themselves; maybe you’re one of them. Some scanty overhyped science seems to show that a modicum of self-talk may be good for you.

But there’s a difference between saying to yourself, “Now where did I put the keys?” and arguing with yourself. I’m convinced that a good argument in your head can let you conquer your own personal Troy.

First, what’s an argument? If you’ve read my first book on rhetoric, you know the difference between an argument and a fight. In a fight, you try to win or dominate. In an argument, you attempt to win over your opponent, reaching a consensus that favors your choice. Aristotle wrote that deliberative argument deals with choices and decisions. It’s what he rather optimistically considered the language of politics.

A good argument changes the audience’s mood,

making it more susceptible to persuasion. Aristotle called this mood “receptivity”; modern behaviorists call it cognitive ease. (I call it the Homer Simpson state. Dangle a rhetorical donut and your audience is yours.) If your audience already trusts you—you’ve established a bombproof ethos—then they’re probably already receptive.

Next, it changes the audience’s mind,

bending it toward your choice. You do this by making the outcome of that decision seem wonderful and entirely to your audience’s advantage.

Finally, it stimulates action.

Create desire. To sell an expensive muscle car to a testosterone-challenged male market, pose a beautiful, logically irrelevant woman next to it.

So how does this all work when I’m alone and balking at a painful workout in the godawful dawn?

As long as I can remember, I would mentally stress-test all my decisions: This could be stupid, I would say to myself. (For some reason I found this to be enjoyable, and it baffled me when I said the same thing to everything my siblings said.) I was just putting both sides to the test. But while this made for a good logical exercise, it did little good for gaining healthy habits. And my default outlook on life had been so pessimistic that my exasperated 18-year-old son once called me “Eeyore” during a weeklong backpacking trip.

Then one day my wise wife suggested I turn the tools of rhetoric onto myself. This would require persuading an audience that happened to be me.

As if I wasn’t eccentric enough.

Still, being the loving, obedient husband that I am, I took a deep dive into the books of Aristotle I had ignored in the past, and…eureka. I found my self-audience in his wonderfully strange book, On the Soul.

Aristotle describes the soul as a kind of organ in your body, or possibly something outside you that connects you to the universe. (Descartes later located the soul in the pineal gland. Now you know.) The Aristotelian soul is an ideal version of yourself, representing your greatest values and wisest choices. This, I realized, was my audience. Instead of just talking to “myself,” I would persuade my soul. I experimented with the great manipulative tools of ethos, pathos, and logos, all to persuade myself that I was worthy of my superior soul.

That’s the subject of my latest book. To be honest, some of those techniques failed to work all that well. I found it hard to convince my soul of my pure disinterest (eunoia in Greek); and my attempts at humor failed to land while doing pull-ups at 4:30 in the morning. But a surprising number of tools did work, from rhythmic paeans to inductive rhetorical logic to Aristotle’s Lure & Ramp.

The arguments in my head keep getting better, and they’ve made me a good deal less Eeyoresque. At the same time, they prime me for persuading clients and, occasionally, loved ones.

Best of all, rhetoric leads to choices without anger. These days, I’m much less angry with myself. I’m thankful for arguing.

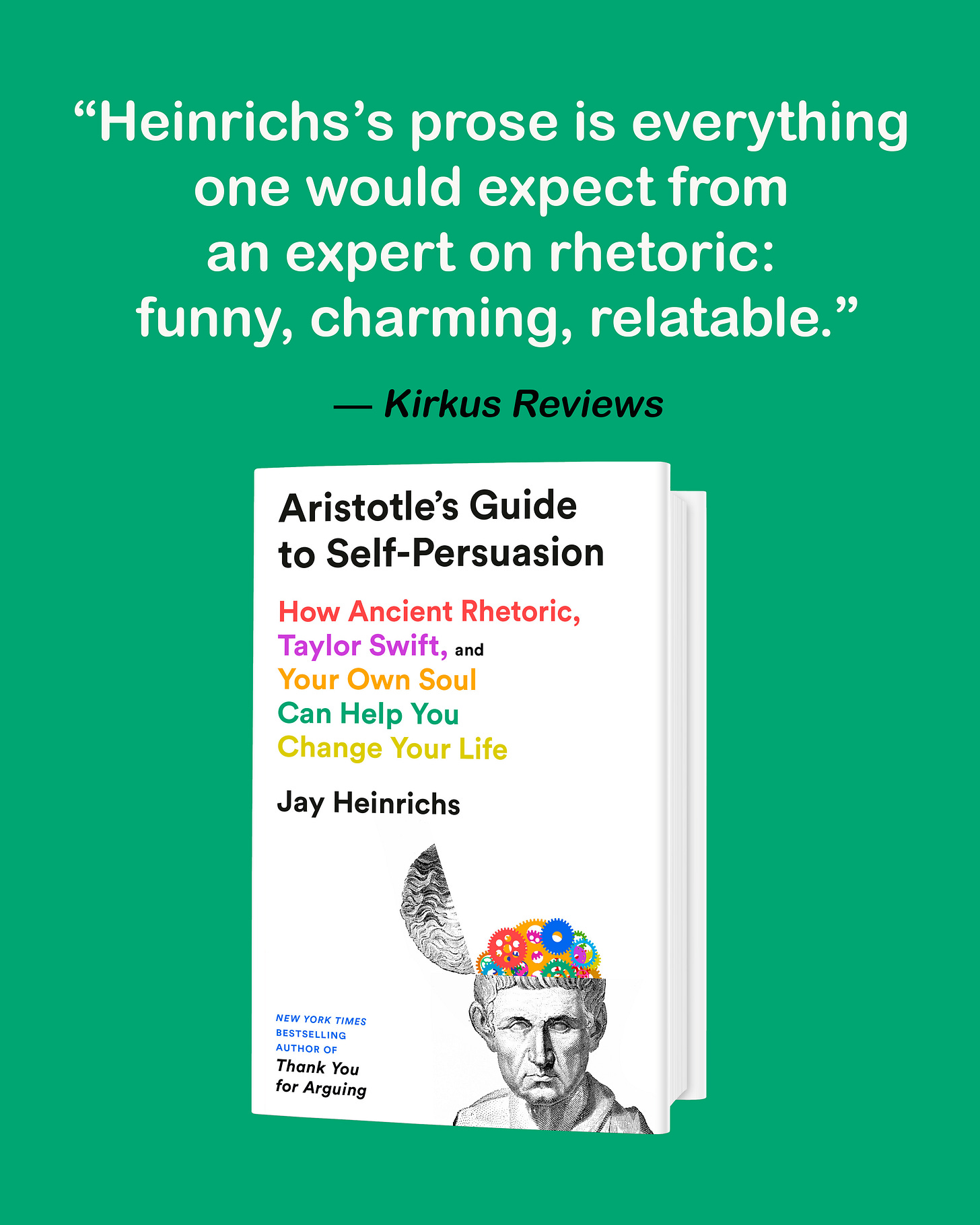

While this newsletter will remain free, please consider supporting me by buying a book.

A great idea. I think the illeism journaling technique of antiquity is this idea put in written form: https://open.substack.com/pub/andrewperlot/p/how-to-journal-like-a-philosopher?r=1xulhu&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

SO perfect and enabling for where I'm at. In my crusty old guy retirement from the day-to-day, I do little but talk to my wife or, when she tires of that, myself during all waking (even sleeping) hours, occasionally scribbling down what's afloat up there in the noggin. Then I go take a swim and talk to myself when sudden bubbles indicate I'm trying to say things aloud and better not— never a good idea. Gotta read the Odyssey again. That guy knew water.