Magic in the Great Green Room

You will find almost all of rhetoric's power in this one children’s book.

Don your foot pajamas, children, and I will show you the magic of rhetoric in an argument between an elderly babysitter and an anthropomorphic rabbit. It all begins in a great, green room…

I’m perfectly serious. If I were to teach another course in beginning rhetoric, I would start with Goodnight Moon.

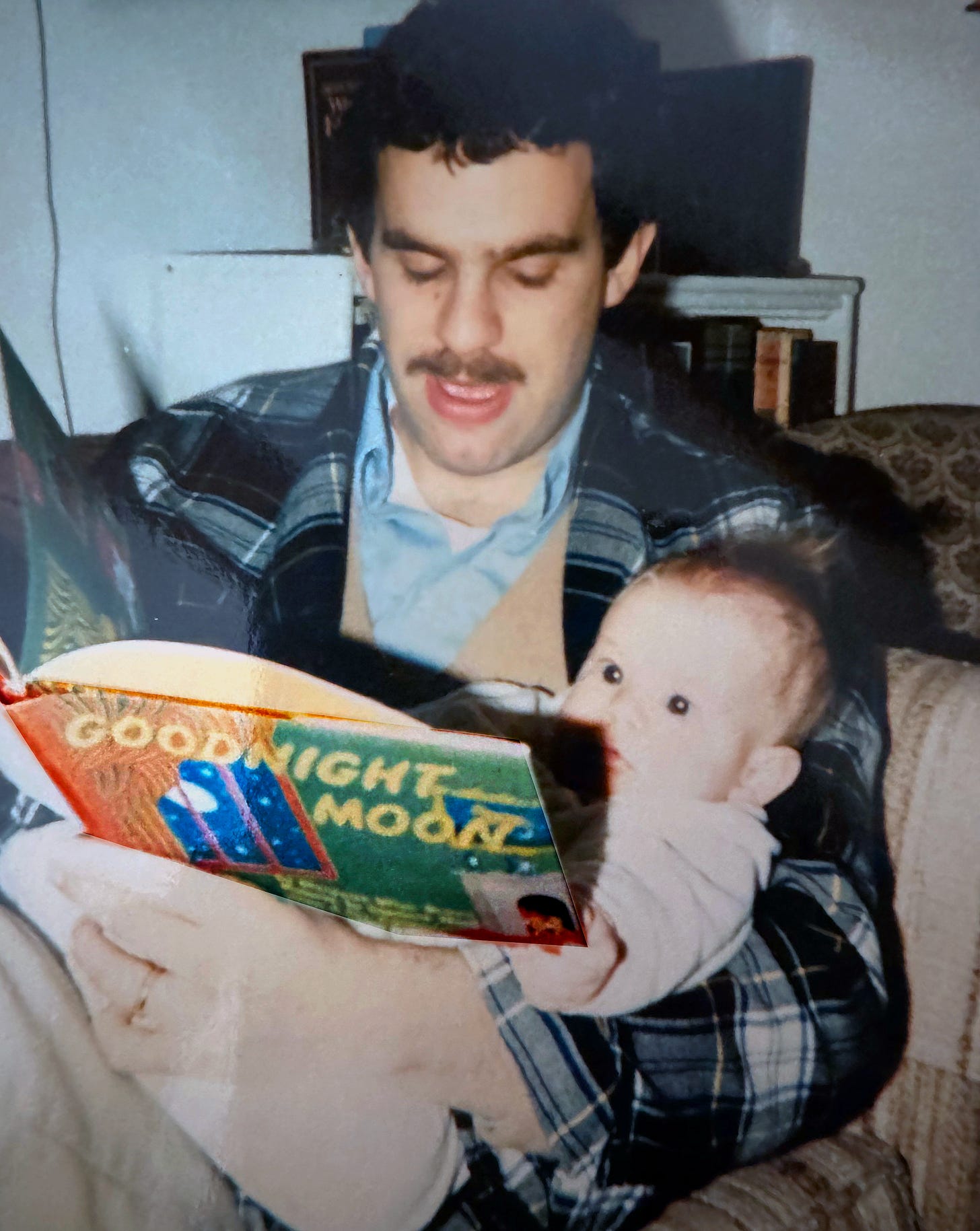

The book contains the most important elements of rhetoric. When my children were little, I read Goodnight Moon to them so many times that to this day I can recite it by heart. It’s been kicking around in my head for years, and I keep discovering new rhetorical delights hidden within that brilliant little illustrated poem.

It would take me an entire term to cover all of what I found in Moon. But here’s a taste. (I’ve included the text at the bottom of this post.)

Exigence and the rhetorical occasion

Rhetoric starts with the persuader’s desire. That need or purpose is called the exigence. So, what do you think is the exigence of the old lady? What does the rabbit want? How do they conflict?

While we’re at it, what about the author’s exigence? What does she want to accomplish with this book? Obviously, her original exigence was the need to sell books. That helps explain why Margaret Wise Brown and her illustrator, Clement Hurd, placed Easter eggs of their previous book, The Runaway Bunny, in Goodnight Moon. Which gives us a struggle over bedtime and a subtle marketing ploy.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, the great rhetorician and politician in ancient Rome, said that the most important question to ask of any persuader was: Qui bono? Who benefits? Who gets rewarded most by the choice a persuader wants the audience to make?

In Goodnight Moon, who benefits from hushing?

Every rhetorical strategy starts with the particular occasion: Where are the words being read or uttered? Who’s saying them? Who’s the audience? And what do they all want?

Narrative

Given that Goodnight Moon has sold more than 48 million copies, it seems surprising that it failed to get a good initial reception. Only 6,000 copies sold when it first published in 1947. The influential children’s book librarian at the New York Public Library refused to stock it; Goodnight Moon reportedly got welcomed to the library’s shelves only in 1972. Why the gap? The librarian thought the book was too “sentimental.”

Sentimental? Really? To me, the plot borders on the tragic. This tiny child occupies a vast, parentless room. And what is that telephone doing in a child’s bedroom in 1947?! Somebody in Wikipedia wrote that the phone proves this was a parent’s bedroom; in which case the adults have quirkily furnished it with nursery-rhyme art and a child’s bed…

Of course it’s the kid’s room. It’s a nursery. Does the phone indicate the Forties version of the nervous Millennials who give their toddlers smartphones? Or is the instrument an excuse for wayward parenting? Margaret Wise Brown’s own parents had an unhappy marriage, and they shipped her off at age 13 to private school in Switzerland. Is the bunny the literary relict of a lonely little girl? “Goodnight nobody,” the bunny says toward the end. Is the poor creature running out of material, or is this an existential cry for help?

(It would freak out my grown kids if I shared this interpretation with them, and maybe I will.)

Storytelling gets an audience to participate in the persuasion. It sucks them in. The danger comes from the audience’s interpretation. It’s up to them to find the moral of the story. Every narrative constitutes a kind of Rorschach blot. You can use storytelling to hold their attention, but the movie in their heads is their own.

Audience theory

Every good argument fits the persuasion to a particular audience. The quiet old lady’s argument fails because it lacks any incentive. Aristotle would say it’s not “advantageous” for the bunny demographic.

“Hush.” That’s it? Just “Hush?” No thank you.

The child for its part wants to delay bedtime. So, instead of arguing directly with its opponent, it speaks to the objects in the room. The old lady wants the kid to go to bed. I am going to bed, its actions imply. Which leads us to the next rhetorical tool…

Framing

The bunny brilliantly reframes the issue. Saying goodnight to everything does not constitute a hushing violation; it’s an essential part of the process of going to sleep! The frame shifts from a sleep failure to the maintenance of high bedtime standards.

Every parent has seen this stalling tactic. When my son, George, was little, he would ask for “two more pages,” then another two. He negotiated more awake time by framing it within the literary experience. These days his own two-year-old daughter instinctively uses a similar technique. So does my cat.

Figures of speech

A catalog efficiently lists items—phone, balloon, bears, kittens, mouse, wall art—to create a scene. The anaphora figure repeats the first word or phrase (“Goodnight…”) in successive clauses or sentences. Alliteration and assonance—repeated sounds—help create a mood. Great, green room, telephone, balloon, cow, moon, all create a yawning effect. Reread those words and try not to yawn.

Tropes

Tropes act like small children; they play pretend. The child speaks to stuffed bears, live kittens and mouse, and even the moon as if they were bedtime companions. It practices personification, a trope that lies behind every AI chatbot.

But wait: the child is a bunny. Illustrator Hurd admitted that he wasn’t very good at drawing humans. The result is a form of personification, anthropomorphism, which turns rabbits into children and old ladies. All this pretense could be seen as irony, one of the core tropes. Is the kid being a bit ironic when it bids goodnight to everything in the room? Is it feigning kindness while stalling?

As for the old lady, she’s a synecdoche, a trope that uses an individual to represent a generic group.

Tense

Did you notice how the poem shifts from the past tense to the present?

Aristotle divided types of rhetoric around the tenses: past, present, and future. The past tense is great for once-upon-a-time storytelling, while the present tense (epideictic or demonstrative rhetoric) brings the tribe together. It’s the rhetoric of public prayer, among other things.

The bunny does give a sort of prayer. A review in the New Yorker cleverly labeled Goodnight Moon “a hypnotic bedtime litany.” A litany is a kind of chanting prayer traditionally done by Christians. Best known is the “lesser litany”:

Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison.

Lord have mercy upon us, Christ have mercy upon us, Lord have mercy upon us.

As with any good bedtime prayer, the rabbit’s version contains a repetitive catalog:

Goodnight bears

Goodnight chairs

Goodnight kittens

And goodnight mittens

It’s the equivalent of a typical childhood bedtime prayer:

God bless Mommy and Daddy, and my cats Killick and Mudgett, and maybe my brother George if you want...

All this gets expressed in present-tense demonstrative rhetoric—aka sermonic rhetoric, because it’s also the language of sermons.

Pathos

Rhetorical pathos seeks to control the audience’s emotions. A father reading Goodnight Moon aloud tries to lull his little audience to sleep. So does the old lady.

Ethos

Seen through the eyes of the spoiled little rabbit, the babysitter is nothing more than a generic old lady. She gets no respect.

A powerful ethos would have the young audience believing she’s a skilled bedtime ruler, that she has the child’s own interests at heart, and that the two of them share the same values such as the proper time for sleep. I call these values Craft, Caring and Cause. The old lady lacks all three C’s.

Logos

This is the one rhetorical tool lacking in the book, which is no surprise. As Aristotle wrote, logic rarely persuades.

Early critics of Goodnight Moon flamed the book for being uneducational. It doesn’t teach anything, they said. But I’m hoping you can see that it has a lot to teach, at least for adults.

As for children, well, you decide. The critics pointed out that the story never leaves the green room. It fails to explore, they said. My kids explored every picture and followed the rabbit’s progress passionately. You tell me whether that’s educational. A rich story in a single room opens all kinds of imaginative possibilities. Does that qualify as education?

Actio

That Latin word means “acting” both in the active and theatrical senses. The rabbit’s goodnight litany is a perfect example of actio, rendering a series of blessings as an argument against sleep. The kid takes agency throughout the book, refusing to eat its mush while blessing the objects in the room.

When I read to Dorothy Jr. and George, I played the part of both the old lady and the young child—acting the roles while taking action through my quiet voice to tranquilize the kids.

Repetition

In the year I spent experimenting on myself with various tools of persuasion—the subject of my next book—I found repetition to be one of the most powerful tools. Repeated words and thoughts literally change the brain. They create a slightly different reality, and, as the ancient Romans put it, bend souls. In repeating “Goodnight” to each object in the room, the rabbit establishes relationships, fostering belief in their living personified reality.

I’ll be doing posts about repetition in the future. It’s soul-bendingly mind blowing.

Memorization

The ancients ranked memory as one of the top skills to hone through education. All stories begin with memory. The mother of all the Muses was Mnemosyne, goddess of memory. I wouldn’t have written this post if I hadn’t accidentally memorized Goodnight Moon all those years ago.

In college, I learned that memorizing the poems in Robert Pack’s American Poetry course would help me get an A. Decades later, I don’t remember the lectures so much as some of the poems themselves. I still recite a few in my head when I’m hiking alone. They let me chew the literary cud; the poems seem different every time I chew them.

If I were to begin a course on rhetoric with Goodnight Moon, I would strongly encourage the students to memorize it. The effort would be good for their rabbity little souls.

Goodnight Moon

by Margaret Wise Brown

In the great green room

There was a telephone

And a red balloon

And a picture of

The cow jumping over the moon

And there were three little bears sitting on chairs

And two little kittens

And a pair of mittens

And a little toy house

And a young mouse

And a comb and a brush and a bowl full of mush

And a quiet old lady who was whispering “hush”

Goodnight room

Goodnight moon

Goodnight cow jumping over the moon

Goodnight light

And the red balloon

Goodnight bears

Goodnight chairs

Goodnight kittens

And goodnight mittens

Goodnight clocks

And goodnight socks

Goodnight little house

And goodnight mouse

Goodnight comb

And goodnight brush

Goodnight nobody

Goodnight mush

And goodnight to the old lady whispering “hush”

Goodnight stars

Goodnight air

Good night noises everywhere