Meet the Feghoot, a pun-enabled shaggy dog

Tell a story that makes people groan, bogs dark, and Britannia waive the rules.

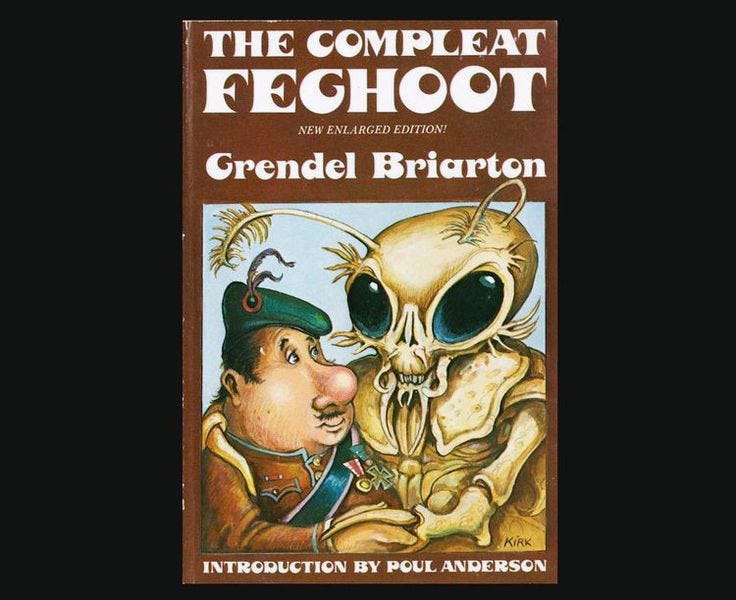

Ferdinand Feghoot was a grotesque little science fiction character invented in the mid-1950s by Reginald Bretnor under the anagrammatic gnome de plume Grendal Briarton. Feghoot embarked on brief intergalactic missions for the Society of the Aesthetic Re-Arrangement of History, with each tale ending in an outrageous, cliché-based pun. (You can find his stories, originally published in various science fiction magazines, in this collected volume.)

Feghoot compositions regularly show up in the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest for gloriously bad writing. Some years ago, Mitsy Rae of Danbury, Arkansas, pulled off an instant classic:

When Detective Riggs was called to investigate the theft of a trainload of Native American fish broth concentrate bound for market, he solved the case almost immediately, being that the trail of clues led straight to the trainmaster, who had both the locomotive and the Hopi tuna tea.

Time magazine managed to turn a news story into a Feghoot when, in 1971, the United Nations let China join the Security Council. Time headlined the piece: China in the Bull Shop. That headline helped inspire me to become a magazine editor myself.

A decade later, I wrote a short news piece about an American scientist named Hale, who had been denied entry into the UK by the British government. After London finally relented, I wrote the headline:

Hale, Britannia? Britannia Waives the Rules.

Unfortunately, the title was almost as long as the (rather trivial) story. My boss rewrote it into something sensible, saying the pun nauseated him. Which just proved he was the bastard of his own ptomaine. (Master of his own domain, see. Yeah, that didn’t work.)

Feghoots aren’t the most useful kind of pun; but they can help you end a story, which is a big problem for many of us. We tell a great anecdote to our friends, get some laughs, and things go great until we realize we have no clue how to bring the thing to a close. What do you do, give it a moral? An alternative, the Feghoot, summarizes your story in a way that makes people laugh; or more satisfyingly, makes them sick.

Sidetrack: Edward George Earle Bulwer-Lytton was the nineteenth-century author who wrote “It was a dark and stormy night.” He also coined “The pen is mightier than the sword,” “the great unwashed,” and “the almighty dollar.” A member of the British Parliament who served as Secretary of State for the Colonies, Bulwer-Lytton was awarded a baronetcy by the king. He counted Charles Dickens among his friends. Richard Wagner composed an opera based on one of the prolific baron’s novels.

Those novels were enormously popular in their day. I’ve read a few and found them surprisingly entertaining. So why do people consider him the epitome of bad writing today? Blame his bitter enemy William Makepeace Thackeray, who made fun of his writing. (In fairness, Bulwer-Lytton started it by first writing a satire of Thackeray’s prose.)

Exercise

Want easy immortality? Fabricate a Feghoot and submit it to the Bulwer-Lytton Contest. To create one, start with the pun. Take a common expression—any cliché will do—and find puns and near-puns for several of the words. Then dream up a story that leads to the conclusion.

You’ll probably find that the punning is harder than the storytelling. For instance, we could use the expression, “The more things change, the more they remain the same.” That can become, oh, L’amour sinks chains, l’amour remains insane. We could tell a story about the screen actress Dorothy L’Amour losing a bracelet; or construct a more elaborate tale about a crazy man who falls in love with a prisoner.

Admittedly, a Feghoot won’t win you friends. But winning the contest is an honor worth…wait for it…a Lytton-y of praise!!! Oh Lord bless me, I’m such a witty cove.

Of the two major costs to producing "AI" engines, only one has been getting much attention. The compute power, and associated energy costs, is well-documented. But real humans need to judge and code responses that the computer produces to "train" the AI to be, well, more human. This involves thousands of people, typically in remote teams working from computers at home. And it involves many millions of dollars in labor costs.

Neuroscientists at Dartmouth hope to automate this too. They can't just ask people "A penny for your thoughts?" and try to get the computer to match what a person says. Science has long known that people’s interpretations of normative behavior (what should or shouldn’t happen) are signaled via m-waves almost instantly, even before the people themselves know their own thoughts.

The team found that developed a brain signal aerial that harvests cerebellum signals before they develop into cogent thoughts. These are then used to code AI engine responses at a speed faster than thought.

“Instead of asking them to think and code their responses, we have something better and faster” said project director Slim Vitae: “Antennae for your oughts."