The 5 Rules of Collaboration

The best partners don't agree right away. Instead, they "bounce."

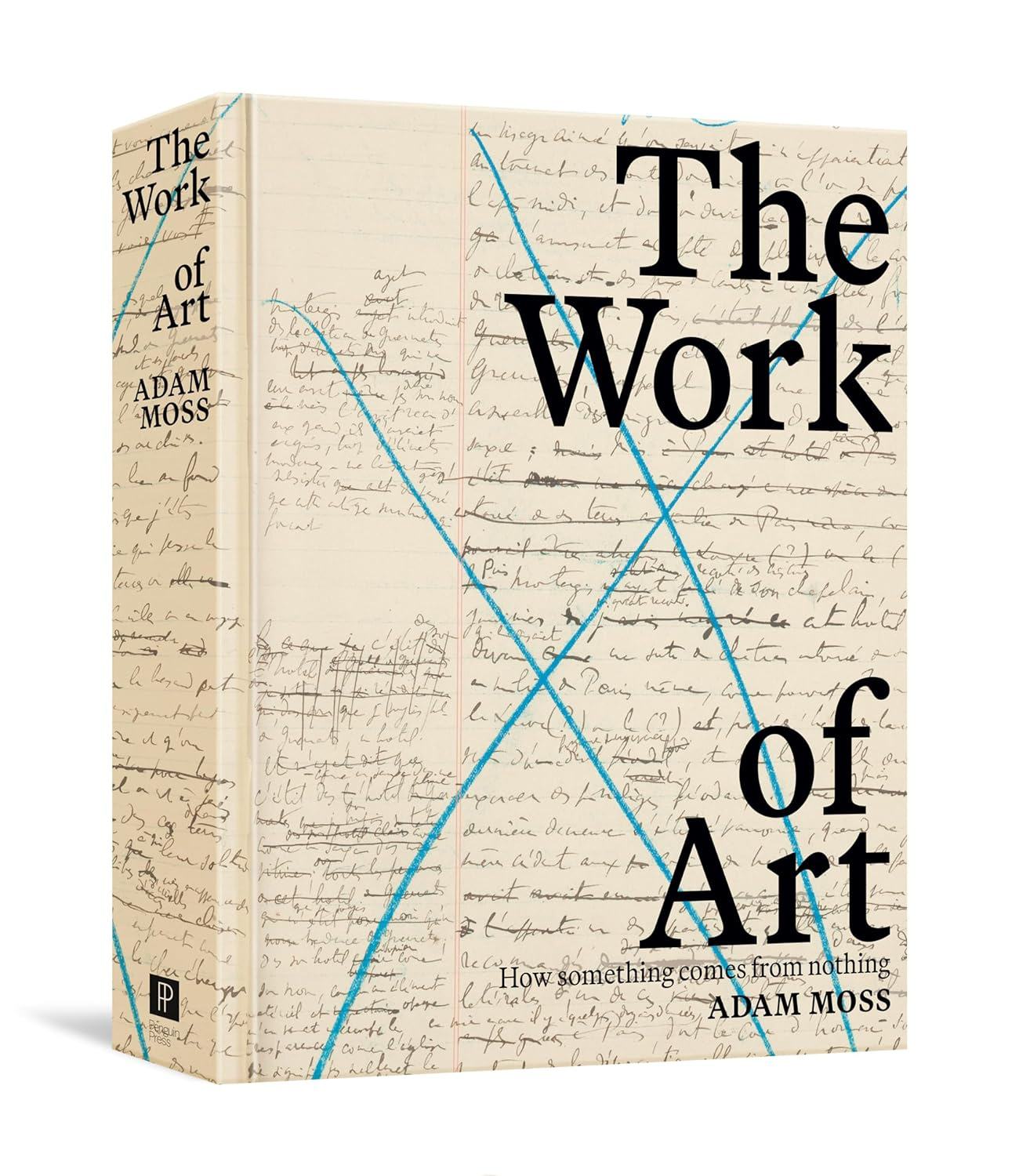

My go-to gift for smart people—I gave it to friends and relatives on Christmas—is Adam Moss’s The Work of Art: How Something Comes from Nothing. Moss, a legendary magazine editor, interviewed artists of all kinds, from painters to sculptors to writers to entertainers, focusing on the process each used.

In one chapter, Moss describes how David Simon wrote The Wire, the greatest series in the history of television. To help write the series, Simon brought in a partner, Ed Burns. With Burns, Simon “would be well served by having a ‘bounce’—that is, he’d work better through ricochet than a solo effort and be a more effective creator if he had someone to tussle with.”

Bounce. It’s the rebound effect of a good argument. And it lies at the heart of Aristotle’s deliberative rhetoric—decision from disagreement. Here’s how Moss puts it:

“The word bounce [is] a noun to describe a collaborator—a person to argue with, who makes you better.”

Simon himself says it’s critical to his creative work:

Bouncing, “with all its back and forth, push and pull—is really the only way I know to do anything.”

I’m a huge fan of Simon, and also of Adam Moss, who made New York magazine the rival and often the superior of The New Yorker. As a magazine editor myself, I miss the days of standing in front of a giant corkboard arguing about layouts and display copy with talented, witty people. While most of us shy away from arguing, I believe that creative disagreement can lead to brilliant creations. The trick is to follow certain rules. (Skip to the end of this post if you can’t wait.)

Successful collaborations are the opposite of groupthink. No one finishes each other’s sentences. Instead, there’s some rhetorical jostling, and things can get pretty heated.

Years ago, I worked with a brilliant, highly argumentative designer, Paul Carstensen. He and I would get into shouting matches that would sometimes upset other staffers, to the point where I decided we needed a safe word—in this case a phrase—to hit the brakes.

Paul and I loved the dialogue in the 1993 movie The Fugitive, when Harrison Ford yells, “I didn’t kill my wife!” and Tommy Lee Jones, playing a pursuing detective, replies, “I don’t care!” So, when Paul and I would get overly passionate about a magazine cover choice, one of us would yell, “I didn’t kill my wife!” The other would dutifully reply, “I don’t care,” and both of us would smile. Meanwhile, as often as not, Paul’s argument would steer me in a different direction. I’d feel the bounce.

These days I frequently collaborate with Adam Moss’s art director at New York, Luke Hayman—who happened to design The Work of Art. Luke is a partner at Pentagram, the Valhalla of designers. I’ve also done projects with two other Pentagram partners, DJ Stout and Matt Willey. Take a look at their work if you have time; you’ll see what a highly variable art publication design can be. Each collaboration takes on a different tone, but all depend on our different perspectives, and our willingness to express them.

This kind of bouncy argument has made a huge difference to my next book. I just completed the editing phase with my editor at Penguin Random House, Matt Inman. Matt and I argued through the manuscript’s Microsoft Word review feature. His comments were at once kind, supportive, and brutal. He pushed me to cut 10,000 words out of an 80,000-word manuscript, killing my darlings as we say in the writing biz. Our arguments were painful, at times humiliating, and I sort of loved it. It was like playing tennis with a pro. Matt made me better.

Here are some rules for great collaborations:

1. Have a safe word.

Before you begin arguing, come up with an expression that stops everything and makes you smile. (“I didn’t kill my wife!” “I don’t care!”) Silly as this sounds, safe words keep everything meta; this isn’t about egos or the future of the planet, it’s about the creation! A safe word might also help a relationship, marriage being the ultimate collaboration.

2. Consider making it improv.

If you’re uncomfortable with David Simon-style debate, employ the “yes-and” technique of improv comedians. Your partner says:

“We should build all this around the color red and call it ¡Caliente!”

You hate this idea, but instead of saying so, you reply:

“Brilliant! And let’s look at other colors as well. Like, ¡Azul! And maybe we can think of other ways of doing a Spanish theme.”

3. Make sure there’s a boss.

After all the bouncing, one of you has to make a final decision. When I work with a Pentagram partner, I push hard for my ideas but ultimately bow to the designer’s greater wisdom. In any work with a deadline, you can’t just agree to disagree. “You’re the boss” is one of my favorite expressions. (I just wish my children used it more often.)

4. Praise and thank at the end.

If you happen to be the decider, don’t forget to express gratitude for all that arguing.

5. Trust the process.

Argument is important to any collaborative creation, not to mention conversation. Arguments can get uncomfortable. But shying from fruitful argument leads to bad decisions and social decay. Look at what happens to social media. Every platform eventually reduces itself to pablum or roaring one-note nonsense, as tribes form and cliches abound.

Look at Facebook and Twitter. Frankly, I can see it already happening with Bluesky and—dare I say it?—Substack. While Substack Notes has far more sensible and interesting content, I tend to see the same cliches, the same jargon, the same political opinions, over and over. Comforting now, boring soon.

The answer, I think, is to treat arguing as a form of collaboration, and to collaborate through argument. Disagree, learn from disagreement, trust the process, and enjoy the bounce. In the end, we all create someone better.

Nerdy etymology addendum: Exactly what is argument?

The English got it from the French, who got it from the Latin (argumentum). According to my beloved Oxford English Dictionary, an argument is:

In mathematics, a measurement or variable; 15th century authors (including Chaucer) referred to the “argument” of planets.

In music, a unifying theme.

In rhetoric, a disagreement; a discussion.

In philosophy, a process of logical reasoning.

In software, the name of an object in a subroutine.

And in David Simon’s and Adam Moss’s world—as well as my own—a bouncing form of collaboration.

Thanks, JP! We should spar/collaborate someday.

Loved this, Jay. I too miss the corkboard sessions. Everything you mentioned is spot on. And you were the all-time master of the good word.