The God of Timing

We're in a kairotic moment, when rules disappear and opportunities open in the chaos.

In a previous post, I wrote about Leonard Cohen and timing. This one tells a far less impressive tale about me…

In the spring of 2001, at the height of the dotcom era, I spent a fine morning staring miserably out of my office window. I was struggling to monetize the Information Superhighway, a chaotic medium with burgeoning traffic and no directional signals. Back then, no one knew how to coax large audiences onto the Internet without blowing millions on Super Bowl ads. (Remember Pets.com’s creepy sock puppet?)

The company I worked for had a better idea: We would harness the power of radio! We offered a free templated website for each radio station, and in return the station would run commercials driving listeners online. My company made money by selling banner ads and hawking stuff like the cool new “filmless” digital cameras, sharing the revenue with the station. We built some two thousand networked websites and planned to dominate the Internet. The stickier we could make the sites, gluing millions of eyeballs to us, the more money we would make from the ads and products.

That’s where I came in. My job was to gin up compelling content that would keep users coming back. But it immediately became obvious that our market wanted something my tiny staff and I were in no position to deliver; they preferred content about themselves and their local music scene. Our model was unscalable. I was unscalable.

Clearly, I was missing something—a solution allowing a content staff of four and a team of programmers to appeal to millions. Wasn’t this the modern computer era? Wasn’t this the World Wide Web for crying out loud, where creative Internet-industry people like me were destined to raise humanity to a whole new level? Big ideas were out there, just waiting to be turned into instant game changers. And so I gazed out of my generic suburban Connecticut office as if the answer floated just beyond the parking lot, my one shot to become a hero and make billions.

That fall the dotcom bubble burst, our funding dried up, and I was unemployed. The following year, a Canadian computer programmer named Jonathan Abrams founded Friendster, the first big social-networking site. It boasted a million members within three weeks. The year after that, Tom Anderson begat Myspace, then Mark Zuckerberg begat Facebook and Jack Dorsey begat Twitter and thus was born the fabulously lucrative virtual world of social media and its 3.8 billion users. My forehead smack could have been heard in Silicon Valley. This was what I had missed: instead of making content for people, let the people make the content! If that one concept had occurred to me, I might be hobnobbing today with fellow badly dressed billionaires.

So why hadn’t I thought of social media? Few people were given a better opportunity. While Zuckerberg was still in prep school, my company had gathered top programmers, millions in funding, and many millions of radio listeners. Was there some approach or discipline, a way of thinking that would have allowed me not just to spot such an opportunity but to seize it?

Years later, I found just such a method. It was invented almost three thousand years ago by a brilliant group of educators and consultants, who in a nice bit of branding called themselves Sophists, the “Wise Ones.” I discovered their theory while researching my first book on persuasion, Thank You for Arguing. Realizing that the skilled leader knew not just what to say but when to say it, they came up with an art of timing. It eventually became a whole philosophy of opportunity called kairos.

Kairos (KI-ros) is an ancient art, a habit, a set of skills, and a god. It aims to give users a predator’s sharp sense of timing, helps them triumph from past mistakes, and turns the future into a ripe fruit. It has even made some people fabulously wealthy.

More important, kairos theory works best in the worst of all possible times. Chaos creates gaps. (In fact, the original Chaos was an empty, formless space, a gap.) Kairos has to do with the right action at a critical time. When the ancient poet Horace wrote Carpe diem, he didn’t mean “Seize the day,” exactly. A better translation might be “Pluck the day.” You want to bite into an opportunity like a pear before it spoils. A ripe occasion—such as the brief moment before dotcoms became social media—is what rhetoricians call a kairotic moment. It’s a time of change, of decision, a boundary between reality and possibility.

Do I have to tell you we’re in that period now? The rules aren’t just changing, they’re disappearing. Doors are closing, others are opening. We’re in a kairotic moment.

The Bible’s Ecclesiastes is a kairotic poem (“To every thing there is…a time/ for every purpose under Heaven.”) A comedian who jokes about a tragedy and then says “Too soon?” acknowledges kairos. When an officer at the Battle of Bunker Hill shouted, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” he was being kairotic. Strike while the iron is hot. Make hay while the sun shines. Time and tide wait for no man. Many of our best clichés are kairotic.

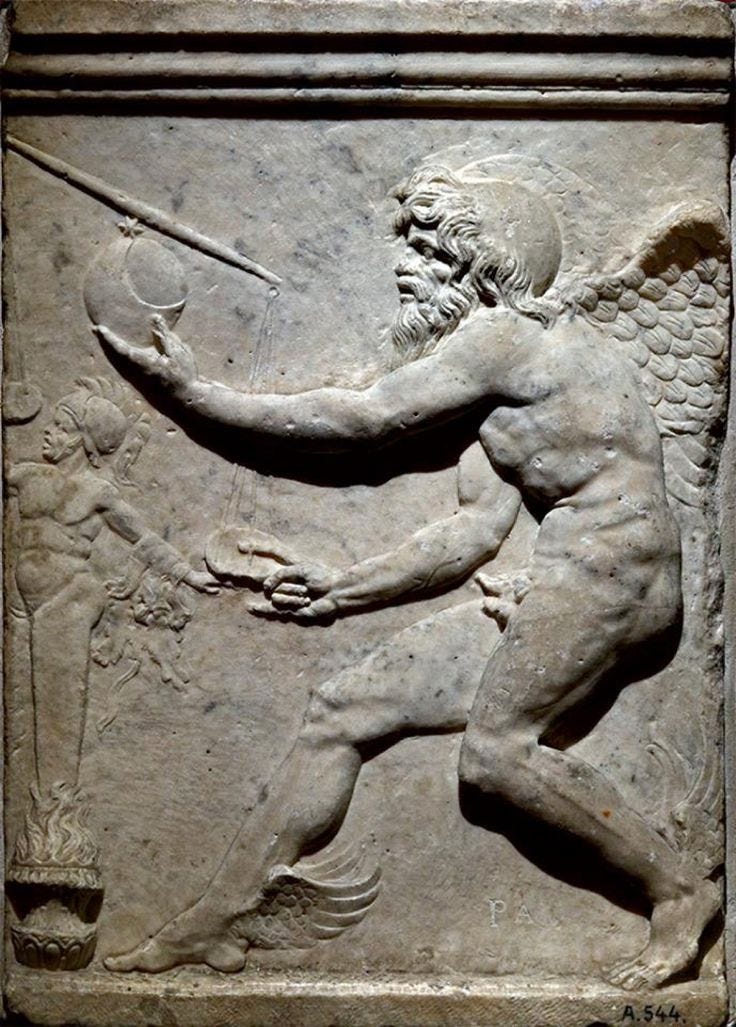

The ancient Greeks were so enamored of the concept that they began worshipping a god named Kairos, who was in charge of opportunity and occasion. (The Romans later called him Occasio.) The great sculptor Lysippus portrayed Kairos as a beautiful young man with winged feet who stood on tip-toe as if running a race. While the god’s hair grew fashionably long in front, if you walked behind him you would discover that the back of his head was completely bald.

The sculptor was making a point: opportunity ages quickly. To meet Kairos, one contemporary poet wrote, you have to take him by the forelock before he rushes by. The question is how.

One secret is to see an opportunity as a gap. The word opportunity itself comes from the Latin portas, meaning “opening.” Gap-spotting is a deeply rhetorical concept involving exigence, a need or problem that focuses every persuasive occasion; as well as the ancients’ marvelously geographical approach to argument.

All to be covered in future posts. Meanwhile, let me know what troubles you most about this chaotic time. We can explore your exigence rhetorically; which, I promise, may offer some comfort.

You just made my day, Gina!

THIS is great: you illustrate, perfect examples, the wildly important points you're making. Nice. I also love turning our attention to the etymology of the words and the distinctions between them. Applause from your admirer, Gina