During my first year in college, I wrote two words that eventually gave me the courage to become a writer. I can’t remember exactly which phrase it was…seismic copulation? Or fornicational geology?

I used one of them, or maybe both, to sum up the famous sleeping bag scene in Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Like many other immature readers, I found the passage both titillating (“He felt her trembling as he kissed her and he held the length of her body tight to him and felt her breasts against the chest through the two khaki shirts”) and hilarious (“And then the earth moved”). Seismic copulation! Fornicational geology! My paper was mediocre, and I knew it; so I was doubly surprised when the instructor gave it an A-plus and circled my seismic phrase in red. “Gemlike!” he wrote in the margin.

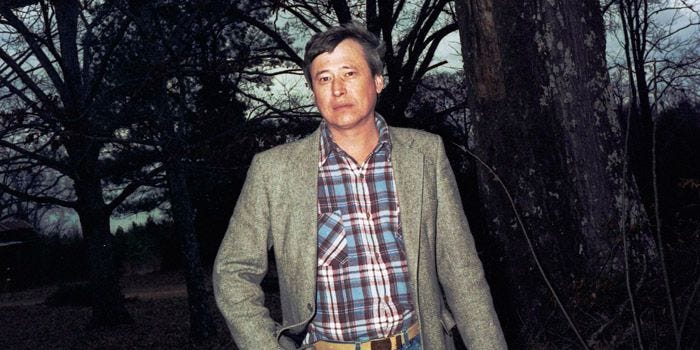

The prof—Barry Hannah, author of the acclaimed novel Geronimo Rex—liked to grade papers at a dive bar called the Alibi. This may have had something to do with his generosity toward me. But, besides the thrill of receiving praise from a famous writer, his comment gave me a flash of insight:

My professor was a phrase man.

I knew that some teachers are sentence graders; they zero in on the best sentence in a paper. The toughest graders are the paragraph types. These are the most careful, detail-oriented examiners. Easiest of all are the phrase people. Barry Hannah was a phrase man. For the rest of the semester, I made an effort to write one memorable phrase into every paper, and I ended up with an “A” for the course.

It turned out that most of the literature professors at my college were phrase people, bless their distracted hearts. Having discovered one of the secrets to gaming the academic system, I diligently crafted key phrases right up through senior year. You could say I was cheating, giving my education short shrift. But four years’ concentrated rewriting of phrases and short sentences did more for my eventual career than the courses themselves.

Why? Because every memorable set of words contains a pith.

You can express a lot in a few words, and those few words can help direct your thinking into greater complexity and originality. Focus on a few words, and you focus your thoughts as well. When you prepare to argue with someone, present a proposal, or give a talk, this kind of focus helps frame your point. Coming up with those few words also makes for a first-class exercise in rewriting.

We learned in school that words are a product of thinking.

Thoughts first, then words.

Our teachers told us to capture our thoughts in a rough draft and clean it up later. This isn't a bad technique; it certainly helps relieve writer’s block. But it's not the only method, or even necessarily the best one. When you want to come up with something memorable—not just original phrasing but an original thought—try starting with the words.

Words first, then thought.

That’s because there are times when we can only dig our best ideas out of our unconscious by labeling them. Instead of working out the thoughts in your head, start with a single key line. Write it down and then, before writing any other line, try to perfect that one. It doesn't have to be the first line. Think of it as a tagline for a movie.

“Houston, we have a problem.”

“Sometimes love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

“In space, no one can hear you scream.”

Exercise

To get in some practice myself, I like to write six-word reviews of movies in my journal.

Ocean’s Eleven: Clooney robs Vegas. Ten guys help.

Toy Story: Outgrown toys speak with witty product lines.

Avatar: An out-of-body planet rescue.

Try it yourself! Put your six-word review of a movie or streaming series in a comment.

Six-word exercises have grown popular since Smith College’s alumni magazine began a contest for best six-word memoirs. Their slogan: “One life. Six words. What’s yours?” The magazine ran the challenge to honor Hemingway, who mastered the extremely short story genre:

For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.

When I write anything, I try to channel Hemingway—the pithy Hemingway, not the fornicational geologist Hemingway. I’ll type a few words even before doing an outline. That’s the pith. I happened to use the method this morning, finding the pith in just four words:

Write first, think later.

It’s very early in the morning, I haven’t finished my second cup of coffee, and the idea of putting off thinking seems especially attractive. So, instead, I write.

Another way to jump-start writing when you just don't feel like it is to deliberately try to write the worst possible story ever written. Sometimes when you try to be bad, it ends up being good. Or at least funny.