That’s just, like, a figure of speech, man.

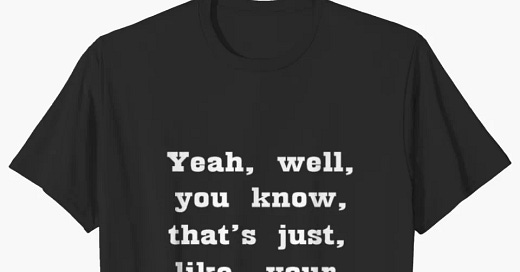

It’s called, y’know, a parelcon, and it really brings a sentence together.

In a previous post, I wrote about how verbing weirds language, in a good way. Verbing has a subspecies (called, technically, parelcon): a word that gets stripped of its meaning and used as a filler.

“Y’know” (we’ll call that a word) is an example, and a bad one. “Y’know” means, um, y’know. I mean, it means “um.”

The word “so,” when used unnecessarily, is another verbing peccadillo.

HE: So when are you coming?

SHE: Well, so I was going to come tonight.

HE: So are you bringing Lamar?

SHE: So who’s asking?

This empty, fruitless talk only reaps all its “so’s.”

In most cases, “like” commits the same crime. Even the brightest college students toss in “like” liberally, like a heart patient oversalting his fries. It’s unhealthy. It impacts language wellness.

Still, we shouldn’t banish the place-filling “like” altogether.” In fact, let’s call it the rhetorical “like.” Used judiciously, the rhetorical “like” serves many subtle purposes. You may not appreciate this next example, but bear with me:

SHE: I told him I was dating Joaquin, and he was like, “You’re what?”

In this case, “like” serves as a disclaimer of accuracy. (“The following quotation is an approximation, and only an approximation, of my ex-boyfriend’s rhetorical ejaculation.”) Young people often use “like” in this fashion to be ironic. It means, “He said that but not really.” It also expresses ironic distance. (“The views expressed by my ex-boyfriend are not necessarily those held by me.”) So, let’s stretch things a little.

HE: So are you, like, freaking or something?

This makes even my teeth hurt a little. But the “like” does serve a purpose—a couple, actually. It inserts a pause, like a rest in music, to place more emphasis on the sentence’s key word, “freaking.” And it gives “freaking” a broader connotation, as in, “Are you something in the nature of freaking?”

So: even meaningless words have meaning. Parelconic place-fillers tend to change from generation to generation. “Y’know” was my generation’s, and “like” is the filler of choice today.

Why the evolution? Maybe my generation was (rightly) uncertain about its ability to communicate. “Y’know” meant, “Are you with me? Do you get what I’m saying?” All through high school, I practiced in front of the bathroom mirror, giving little impromptu speeches without “y’know” in them. (I also worked to get rid of my Philadelphia accent; my wife tells me she still hears it when I’m tired or after two beers.)

While “y’know” shows a lack of confidence, “like” betrays a failure of commitment. It reflects a group too timid to stand firmly on one side of anything. This generation is an ambiguous one, which, from a rhetorical standpoint, may not be so bad. But if you want a consensus, irony has to give way to consensus. That’s impossible if everyone is so afraid of disagreement that they won’t firmly express an opinion.

That’s, like, so wishy-washy, y’know?

Do parelcons ever facilitate effective communication? Are they an annoyance and distraction only to those of us of a certain age? Did we use other parelcons that bothered our elders? BTW, I’d never heard the word “parelcon” spoken before I looked it up on-line. How many years does a new parelcon persist in a language? How are they translated into other languages? Parelcons are, like, fun to think about.