The fantods of dank beldams and other bijou words

Would sympathy for an empath make you gladsome?

Gen-Zs think people like me lack rizz, which is totally bouchma, IMHO. (See my earlier post on rizz which, full disclosure, I actually kind of like.) Still, the older I get, the more I find myself cringing at youngsters’ tribal use of jargon. Can you blame me for my idiomatic reticence? It’s hard out there for us antiquarians. I mean, how can we keep up?

Is anyone on fleek (extremely stylish) anymore?

What happened to the millennials’ beloved yeet (expression of strong emotion; or, bizarrely, a verb meaning to throw forcefully)?

Do gen-Z’s still use dank to mean “excellent,” the way my generation used bad to mean good?

And when I say “You bet” to someone who asks for a favor, should I get all gen-whatever and shorten it to bet?

Why can’t our beautiful centuries-old English language stay stable and pristine? After all, the French still have their Academy of the Forty, whose noble task is to maintain the purity of their language. The Germans and Italians have their own versions of august lexicon keepers. What about English?

English has the opposite: the constantly evolving Oxford English Dictionary. More than a mere wordbook, the OED represents a revolutionary linguistic philosophy. Unlike any dictionary that came before, the OED leads with the belief that all our words—and the entire history of those words—should be available to everyone. Every time I hear a newly coined word and lament the decline of civilization, I find myself saved by this remarkable invention.

Before the OED, dictionary writers attempted to “fix” the language in place. Any word that they excluded, or any definition that strayed from the dictionary’s version, would be “improper.” Early dictionaries separated right from wrong and divided the right-thinking sorts from the hoi polloi. The founders of the OED had a radically different idea. English, they argued, could not possibly be fixed. It changes; it evolves. A word’s meaning strays from mouth to mouth. By printing the biography of every English word, the OED would help readers understand the history of thought in its minutest detail. It was the greatest lexicographical feat in human history.

Aristotle would understand. He knew that the world is anything but static. Life is contingent. But that hardly makes the OED meaningless. Our changing world makes it all the more important to understand what went before. And nothing offers us insight into the minds of literate Anglo Saxons, Renaissance poets, and Pidgin speakers than the history of words and their uses. As Socrates knew, the single most important philosophical question is “What do you mean by…”

A rich vocabulary lets you control the frame of any argument. (If you haven’t read my post on framing, you’re in for a world of glossarial power!) Even more important, a yen for etymology can lead to a more precise understanding of the world.

Take just one example: The difference between empathy and sympathy. We know from Star Trek that an empath is a person capable of a kind of emotional telepathy.

The OED places the first published use of empathy in 1956, within a short story in New Worlds, a British SF magazine. The author, J.T. McIntosh, makes his empath character sound like a human Alexa.

“How exactly does the government use empaths?” Tim shrugged. “We can tell the level of a man's loyalty just by meeting him. We can walk around a factory and sense that there's going to be a strike.”

But when we pursue the word further, we find empath to be the wrong word. Empaths should be called sympaths. Empathy has to do with having a deep understanding of others’ emotions. Sympathy shares those emotions.

People continue to confuse empathy and sympathy. Why does it matter? Because empathy lets you deal with other people’s emotions, while sympathy just makes you suffer them. Few people would call Donald Trump a sympathetic character, but he clearly understands the frustrations of his voters. Does he share their suffering over the price of eggs or their confusion over gender pronouns? If anything, he enjoys their suffering. But he understands it. Democrats could call him an empath and condemn him for it.

We lexicographical antiquarians can make the youngsters salty by bringing out some obsolete words. I’m personally fond of fantods. This synonym for heebie-jeebies seems to have cropped up during the 1800s. Herman Melville’s Ishmael uses the word. So does Huckleberry Finn. I put it in a novel, giving the fantods to a lover of Melville.

This time of year, I enjoy another word worth reviving: apricity, the warmth of the sun on a winter’s day.

Bertie Wooster, for his part, loves to use the word bijou, meaning jewels, trinkets, or anything fancy. It comes from the French bisou, a ring with a jewel. You can use it as an adjective (Trump’s bijou lair in Florida) or as a plural noun, bijoux, for a drawer full of costume jewelry.

A bijou is the sort of thing a fizgig would wear, pardon the etymological sexism. (OED: “A light, frivolous woman, fond of running or ‘gadding’ about.”) Most social influencers—men, women, and others—could be labeled fizgigs.

On a more senior level, we might want to call an elderly woman a beldam, from the Middle English meaning more or less “grand lady.” That’s better than another archaic old-lady term, gammer, from “grandmother.” And either one beats crone in my book. (Full disclosure: some modern dictionaries define beldam as “an ugly woman”—which says more about the dictionary writers than about grownup females.

I happen to be married to a beldam.

To learn the full wonderful story of the OED, read The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary, by Simon Winchester. It got made into a so-so film starring Mel Gibson and Sean Penn; read the book instead. Winchester notes that the OED saw its first full publication in 1928, eighty-four years after the British Philological Society first proposed it. The genius of the dictionary would be its reliance on published quotations. Its editors wouldn’t prescribe “proper” meanings but would apply inductive logic to the task, extracting definitions from each word’s previous use. Thousands of volunteers and dozens of researchers delved into English usage dating back to Anglo Saxon and ancient Greek. J.R.R. Tolkien was one young employee; eighteen years before The Hobbit, he worked on the etymologies of waggle through warlock.

The original plan was hugely ambitious: four volumes, 6,400 pages, in ten years. The actual effort took seventy-four years and totaled twelve volumes, including one supplement. Even before the lexicographers neared the finish line, they realized they had to stretch the goal even further. Culture changes. Scientific discoveries require new language. The dictionary originally left out the word radium on the basis that it was too obscure to be considered part of the English language. Several months later, Pierre and Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize for having discovered the element.

The dictionary’s hyperbolic attempt—a vast tome compiling every known published use of every English word—had to be re-hyperbolized. (Yes, hyperbolized is in the OED.) A second edition, published in 1989, totaled 21,728 pages in twenty volumes. A third edition is in the works, with hopes of completion in the 2030s. Needless to say, it will be vast. And even then, the work will have to continue if the OED will have any chance of seeming…what? Authoritative? Complete? Could it ever be?

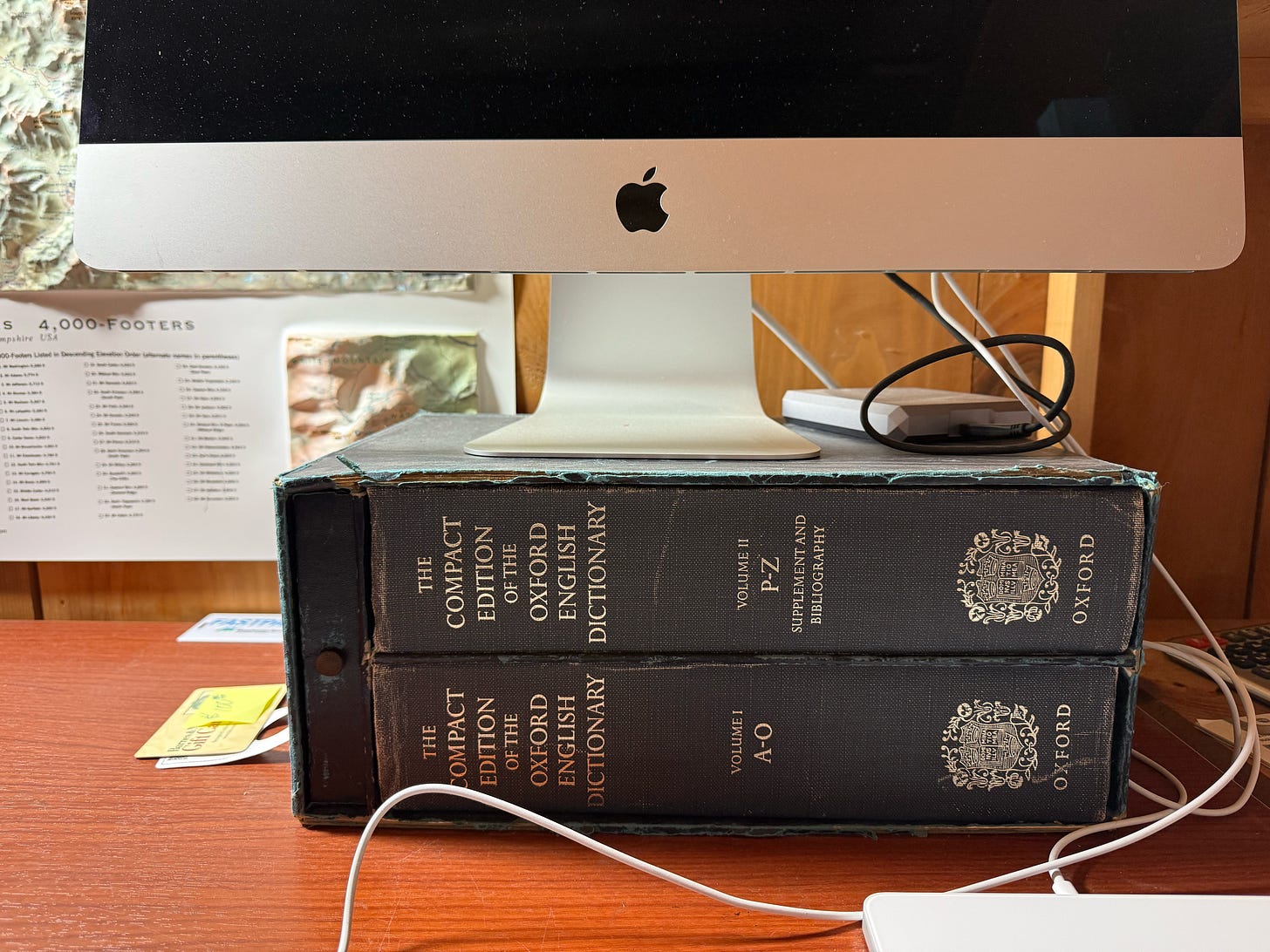

You can still buy a used 1921 compact version of the dictionary, complete with magnifying glass. I have one myself, ironically propping up my desktop computer.

These days I mostly go to OED.com. This is one of the greatest websites ever created, with all the latest etymology, statistics on the frequency of a word’s use over the centuries, and the kind of rabbit-hole etymology that lets you explore the English language as it meanders through individual minds. Full use requires a subscription, but your library should be able to give you access.

The biggest problem I have in looking up a word in the OED is that it leads me from related word to unrelated word and their history and meanings and quotations, and an hour will go by, two hours, without my getting any work done, and I leave my computer larking and gladsome.

What antique word of yours deserves polishing and taken public? Tell me in the comments.

Fantods is a word my students learn in context--I use it when one of their number gives a particularly unnerving response or comments, saying "That gives me the fantods" and moving the discussion along. Great piece today. I have no doubt your other admirers will feel the same delight (bordering on smugness) I'm feeling when I realize I know most of these words. Ain't I bright and erudite? The poll made me laugh. xxx Gina

I agree that language must change and evolve: it has and it will regardless of what people do to prevent that. However, I also think that there are demonstrable benefits to minimizing the rate of change. Without too much help, most of us can follow the texts back about as far as Shakespeare (but that far back gets tricky for many, with even commonly quoted words like 'wherefore' not having the meanings many assume by their similarities to the more commonly used words of today). Almost all books and documents written in English since the U.S. was founded remain readable, but some words from the dawn of our nation may need context to understand, like trying to read something with specific industry or legal jargon.

Now, imagine a much faster rate of change of the language. If people cannot read and understand the books of prior generations because their language has evolved so that 20th century English is to them as Old English (or even Middle English) is to us, that diminishes their ability to learn from the wins and losses of their forebears. Documents like the Constitution cease to be the property of all and become the property of the white tower few who can translate it. It also severs future generations from the novels and fiction of prior generations. I would argue that fiction is one of the best tools for understanding what life was like at the time it was written. Overall, rapid change of language leaves our descendants worse off, with the only benefit being catchier slang.

To your closing question, some uncommon words I like that seemed relevant to this week's article and which I believe, but don't know definitively, were more popular in the past: harridan (vicious old crone), inveigle (persuade), molder (decay to dust over time), recondite (difficult, obscure subject matter), shibboleth (among other meanings, a saying or phrase that lacks current fit with the times).

And on the clever use of a new word (albeit purely fictional), one of my favorite fantasy authors, Stephen R. Donaldson, used the term "caesures" to describe tornado-like storms that damage time and can move people (violently) between times separated by thousands of years. I found this a brilliant bit of word crafting for the evocative sense of the violence and painful nature of a seizure with the meaning of the musical or poetry term "caesura" and pausing time.