We're all chatbots now

But that's nothing new.

When I bring up my use of AI1 to friends and peers, most mumble something about ten-foot poles and change the subject. If I argue with them (and I do love to argue), I hear about school cheating, job losses, deepfakes, apocalypse whenever.

They have a point. One in five students admit to using AI to cheat, and they’re the honest ones. (Another 25% say they operate in a “gray area.”) Too many people with time on their hands are asking robots to create spurious nonsense.

Twice as many Americans think AI will harm them than those who believe it will benefit personally.2 Some of this pessimism comes from the usual discomfort with the new. As Garth Algar says, “We fear change.”

But we’re not going to stop AI. Sure, we should regulate it better—something that definitely won’t happen in the current Congress. Regardless, AI is here, and we’ve barely yet seen what it can do. The trick is to make sure that we copy the so-called AI experts and personally try to benefit from the technology. (Unlike the experts, we might also avoid causing harm. But that’s a different story.)

For writers like me, one solution is to use existing large language models more creatively. AI doesn’t do much original writing; if you consider yourself a pretty good writer, you know to keep it from drafting your essays or ghostwriting your scripts.

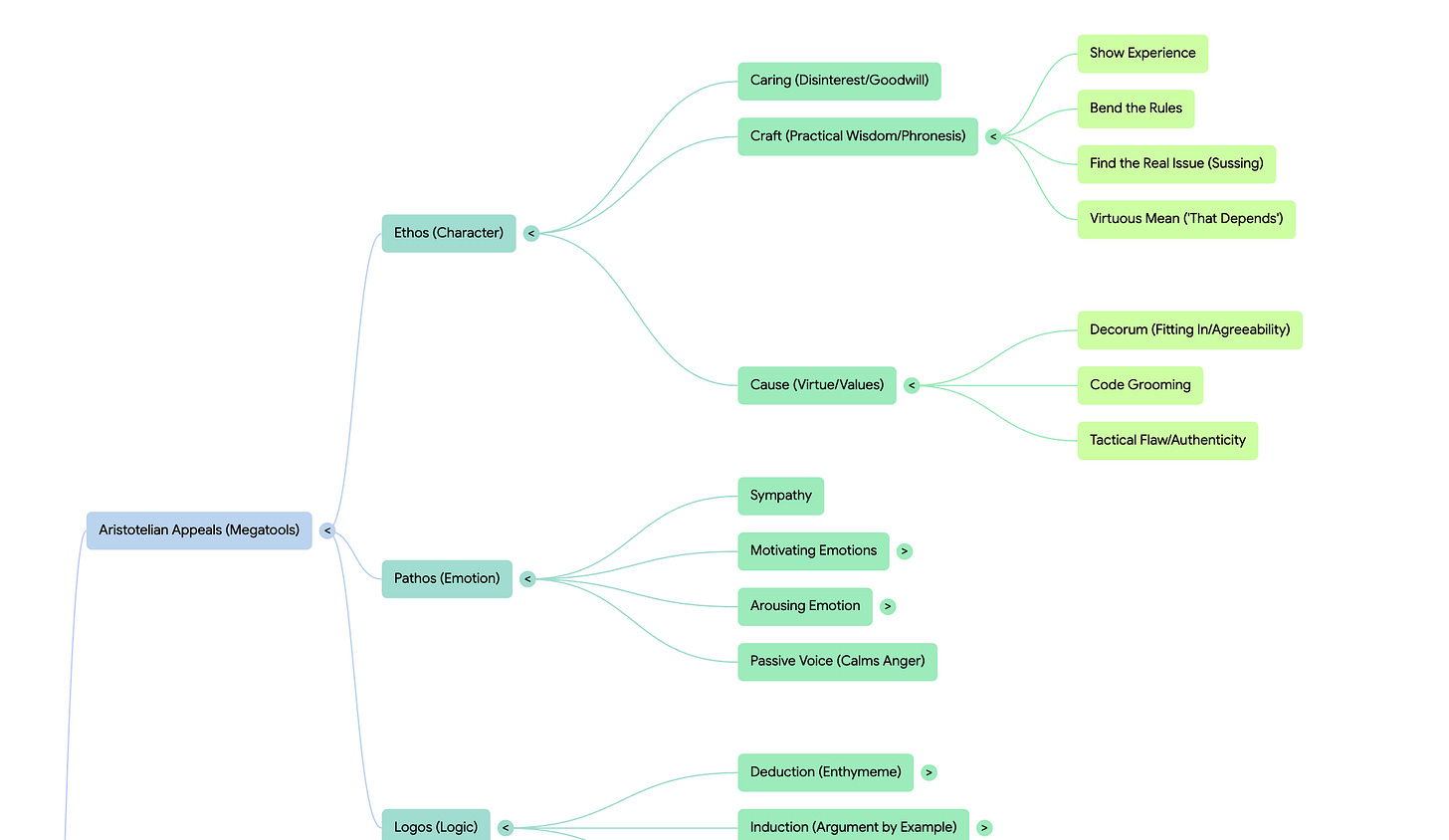

Instead I use various apps as assistants; or, when I’m feeling frisky, collaborators. NotebookLM makes for a great assistant. It organizes everything for me. For instance, I shoved a bunch of my Substack posts into a notebook. Now and then I ask it for potential rhetorical topics having to do with current events. I also use it to create migraine-inducing visuals for lectures.

EXERCISE: Teachers might assign students journal entries—a paragraph or two a day. Have the students query them in NotebookLM. Let them use the app to generate mind maps and visuals. Grade the quality of the queries. Sure, the more cynical students will ask Chat GPT or Claude to come up with prompts in NotebookLM, but that’s an added layer of work. Which requires prompting.

Still, what about the outright cheating? It’s a problem, sure. But AI models already write better than most people. Writers like me consider AI-written pieces to be substandard, but they’re actually standard by definition; AI works with the sum total of what’s out there. Besides, most AI writing reads better than the work of your average scribe. (Including, alas, most of the writers on Substack.3 Face it, most of the “creative” work people aspire to isn’t any more creative than Chat GPT-5’s earlier versions: entirely derivative.

We like to think of ourselves as a creative species. But we’re really more of an imitative species.

We evolved to mimic our parents and steal ideas, whether from fellow humans or clever predators. Instead of merely policing AI, teachers should show how to use it creatively. Many teachers tell me they are doing just that.

At any rate, the problem with students isn’t writing. It’s reading. Show me a bright young thing who doesn’t read for pleasure, won’t read as a habit, and chooses TikTok over books, and I will show you someone who won’t ever write anything interesting.

I would have schools teach nothing but reading rather than to emphasize writing over reading.

Parents should wrestle connected devices from their children’s quivering hands for an hour a day. Buy them comic books and graphic novels, and reward them for working their way up to all-text printed books.

Schools should assign less homework; I hear from school administrators that a lot of cheating starts with the work-pressure kids are under. While we’re at it, let’s not go overboard with sports, a generational problem all its own.

Every school should start a book club, with rewards for students who persuade their peers to read a particular book.

For crying out loud, let’s encourage publishers of YA novels to put out less depressing books. And stop politicians from banning the more interesting ones.4

AI will only get better at writing, to the point where writing will no longer be the best means to foster high-level thinking. Instead we should show kids the mind-blowing delights of worming into the heads of others—writers from different cultures, eras, and mindsets.

That means reading. Some readers—a glorious few—will want to imitate those writers. As they fall in love with still more writers, they’ll try to imitate them as well.5 And eventually, out of that deep mental stew of styles and ideas, they’ll come up with something of their own. Entirely new. Entirely human.

No, I did not use AI to write this piece, though I ask GPT to summarize the data on American attitudes toward the technology. It gave me the equivalent of a high school paper. A bad one. So I hitched my pants up and Googled.

A 2024 Pew study reports that 43% of Americans think AI will harm them personally, 24% said it will benefit them, and 33% wisely say they’re unsure. On the other hand, 76% of AI “experts” believe that AI will benefit them personally. Presumably they have stock options.

The writers I follow on Substack are brilliantly original.

Part of me loves book bans, because they can spark interest in those very books. My mother told me I was too young to read the fancy copy of Bran Stoker’s Dracula on our living room shelf; guess my next late-night reading.

I’m currently reading Elmore Leonard, Mick Herron, and Mark Twain in the attempt to be funnier. If doesn’t work, it’s still a hoot.

Reading this as a creator who actually uses AI, I had a funny double-take. An AI “channeling” Aristotle would probably respond to your piece with a beautifully structured meditation on logos, ethos, and the soul’s surrender to scripted speech… and then there’s me, staring at the screen and saying, “Cool.”

The wild thing is: both are real. The long, rhetorical riff and the one-word reaction are now part of the same conversation. Instead of pretending AI is some imposter at the table, I’ve started treating it like a very nerdy co-host who helps me stretch my thinking, draft the fancy Aristotelian paragraph, and still leave room for my own messy, human, unscripted “Cool” at the end. I’m less interested in poo‑pooing AI and more in asking: what happens when we use these tools to sound more like ourselves, not less?

I pay my kids for book reports for any book that is on the shelf in our house (which there are plenty). At first they pick the shortest easiest thing, then they start working their way through larger volumes, eventually they stop writing the reports and asking for the money, because the reading is worth more than doing the report. #1 Christmas present request is more books. Indecently the opposite is true for video games, they have to pay me to play them.